Exploring Amazonian Gastronomy

If we had to pick just two ingredients to represent the entire Mediterranean culinary landscape, probably “bread and olive oil” would top the list. Its a straightforward storyline there: different neighboring cultures sailed the Mediterranean, exchanged products, and shared culinary wisdom. Let’s say, from Spain to Lebanon.

But what about the Amazon? We often hear about the Amazon fires and its crucial role as the world’s lungs, but how much do we really know about this vast rainforest and its people? Can we pinpoint two signature ingredients that tell a cross-cutting narrative, like “bread and olive oil” in the Mediterranean? Let’s say, from Venezuela to Bolivia.

I was born and raised in Caracas, and I’ve had the opportunity to visit the Amazon rainforests many times, making trips to forests in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Brazil. Additionally, I’ve been actively involved in projects with Amazonian producers.

Let’s begin with Venezuela, where I’d like to debunk some myths and unravel the mysteries that shroud our national identity, starting with our country’s name.

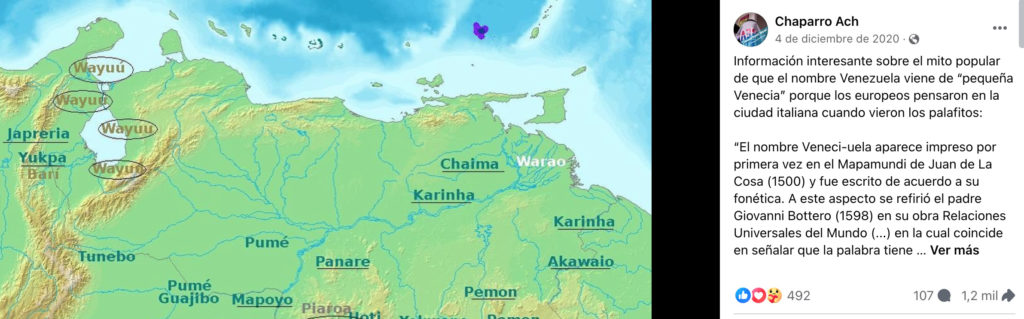

My friend Alex Chaparro has always had an eye for seeking unconventional angles and questioning the authenticity of the socio-cultural structures that shape our lives. I recall a social media controversy provoked by one of his posts.

You see, we Venezuelans have been raised on a story that claims European explorers, upon seeing the stilt houses in Maracaibo, exclaimed, “This reminds me of Venice, but a bit more rustic. Let’s call it ‘Venezuela,’ Little Venice.” And that, supposedly, is how Venezuela got its name. This is still today the accepted theory.

It turns out, in the Paraujanos language, spoken by the people who had first contact with Europeans in modern Venezuelan territory, in their language, “veneci ula” means “big water.” Spanish conquistadors frequently adapted local names to fit the sounds of their own language when exploring new places in the Americas, a common practice during that era. Besides, some of these early explorers were Italians, and the more common expression would be “Piccola Venezia,” which translates to ‘Little Venice,’ not Venezuela.

The Paraujanos’ linguistic lineage rings a bell too; it’s related to the Arawak people, a term familiar from my school days in Venezuela. During my last visit to the Bolivian Amazon, I stumbled upon a revelation that shook my understanding of the continent’s history. A local guide showed me an ancient snake carving on a massive rock in the Beni River region. “It could be thousands of years old, crafted by the Arawak people,” he said. As it happens, the Arawak people were a diverse group that extended from the Caribbean to Bolivia. Indigenous communities had dispersed throughout the entire Amazon region, taking their languages with them.

In a recent podcast episode, I mentioned that I haven’t witnessed the consumption of mushrooms in the Amazon. Well this is incorrect. It’s important to clarify that indigenous peoples across the Amazon have an incredibly deep understanding of nature, including their knowledge of mushrooms. Remote tribes highly value mushrooms for various purposes. They use them as sources of nutrition, powerful tools for hunting, magical elements, protective amulets against dark forces, medicinal agents for humans, and even as adornments for their bodies.

It’s worth noting that modern Amazonian populations are often not direct descendants of the original indigenous ethnicities, as many have undergone cultural assimilation.

Photo: In the Background, Kenzos father 1980s, Tuichi River

Take, for instance, my friend Kenzo Hirose, who was born in the heart of the Tuichi River with Japanese heritage. He represents the modern settlers who speak Spanish, use smartphones, operate boats, shotguns, and machetes. While some traditions have persisted, such as certain recipes or languages, the more complex aspects like the extensive knowledge of mushroom collection are not widely known, just as they aren’t in Europe.

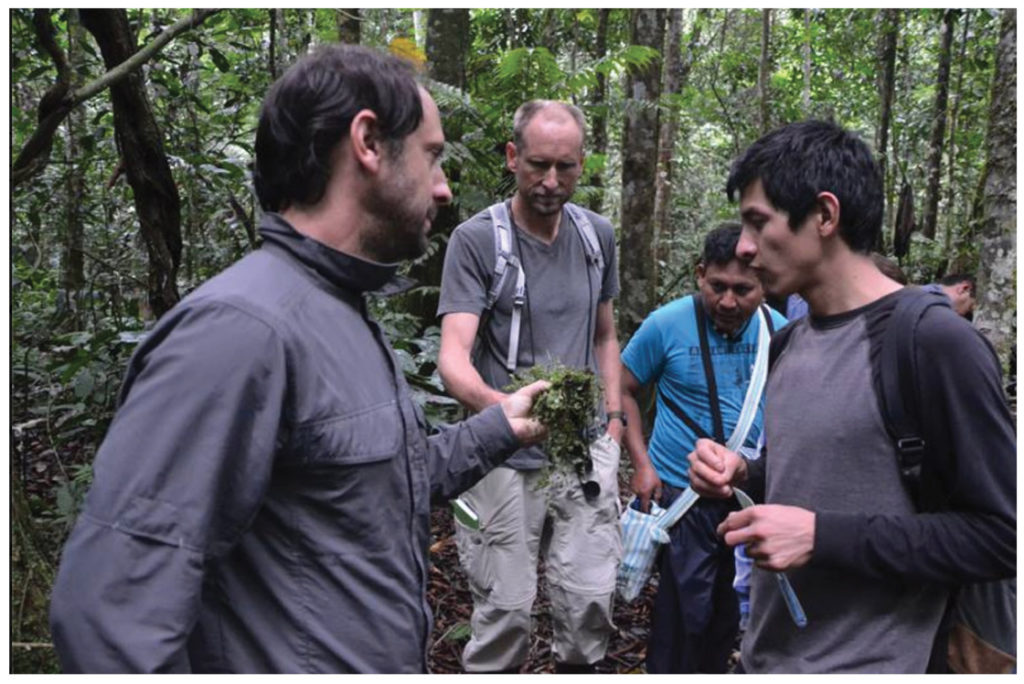

Photo: Pedro Schiaffino, Jacob Olander and Kenzo Hirose Madidi 2015

I had the opportunity to go mushroom foraging with Pedro Schiaffino, Jacob Olander, and Kenzo. Pedro is someone who, when entering a forest, displays an impressive botanical mental library. He collects one after another, lets us taste them, and tells us things like “this one tastes like cloves” or “this one is used for this or that.” He can identify bark, insects, and leaves, and he was the one who pointed out the two mushrooms we would use for dinner that night, which are not commonly consumed by the locals.

I had to choose a flavor that left a lasting impression and seemed uniquely Amazonian, it would have to be the result of an intriguing blend of two ingredients: Ants and chilis. For years, as a kid, I believed, the venezuelan version, known as Katara it was made only from ants. But no, the heat comes from the chili peppers, while the ants impart their distinctive deep, earthy and meaty flavor. Later, I discovered a similar creation in Peru, known as “ají negro” or “black tucupí”, and regional variations across the Amazon, like “tucupí,” a yellow fermented yuca sauce found in every Brazilian Amazon market and even adapted in the pages of Albert Adria’s book “Tapas”, as it was also served in El Bulli back in the days. Pedro Schiaffino shared an experience in which, while setting up a supply chain with a remote community in the Peruvian Amazon and buying their products, he started to generate a more substantial source of income for the women which led to a drama among the male community members. This situation had to be addressed and regulated with the assistance of expert anthropologists, as such conflicts are often encountered.

For me, witnessing Angel Falls or experiencing a starry night in any part of the Amazon is more fascinating than visiting New York City. According to a Study published by Nature, what we understand as the Amazon itself, is a product of human agriculture starting around 10.000 years ago. Researchers examined phytoliths discovered in the Llanos de Moxos region in northern Bolivia. They found evidence indicating that the earliest Amazonian inhabitants cultivated plants like manioc, squash, and maize on artificial forest islands as far back as 10,000 years ago. This suggests that human populations played a crucial role in the expansion of the forests.

Chili itself is another gem that found its way through the Amazon and had its roots in Bolivia. Even today, you can stumble upon wild chili species as tiny as tapioca pearls, harboring only 1 to 3 seeds. The first time I laid eyes on these miniature chilies was in La Gran Sabana of Venezuela, where they grow in the wild. In Bolivia, they go by the name “ulupica,” while in Peru, you’ll find similar varieties known as “charapita.”

These tiny wonders, these ancestral micro-chilies, are the forebears of ALL the chili peppers we know and love today. They originally sprouted from the high-altitude plains of Bolivia and then made their way across the vast Amazon basin. It’s quite likely that indigenous communities like the arawak played a pivotal role in shaping the many chili varieties we enjoy today.

Growing up in Venezuela, “casabe,” an unleavened bread created by local communities, was a familiar staple found in local markets. It’s made from poisonous yuca root, which ancient indigenous culinary wizards detoxified before turning it into this beloved crust. Casabe is prepared by peeling and finely grating fresh yuca, pressing it to extract the juice (yare), and shaping it into a yuca paste. Then, it’s cooked in a hot skillet until it becomes crispy. It’s like a savory, crispy bread crust-like cookie. While the traditional method is still used in villages, industrial production with mechanical presses and circular molds has become common, and pre-made casabe is available in supermarkets and stores.

It was a surprising revelation to find out that Bolivia also has “casabe,” and they use the same name for it. For them, it’s just as Bolivian as it is for us Venezuelans. It turns out casabe can be found in all Amazonian countries, with name variations, much like how you find variations of “bread” in different languages, such as pan, pain, and panne.

Although there isn’t a Mediterranean Sea to facilitate the ancient spread of bread, a network of rivers in the Amazon basin connects Venezuela to Bolivia., where casabe existed long before these regions became countries. But wait, there’s more: the term “casabe” also has its roots in the Arawak language, the ones that lived in “Veneci Ula”. It’s possible that the Arawak people also played a role in developing its culinary process, although we may never know for sure.

For these reasons, my Amazonian counterpart to the European “bread and olive oil,” due to its ancient tradition, enduring popularity, delectable flavor, and wide geographical presence, would be “casabe and black tucupí.”