Dewakan Dinner: Last Waltz in Kuala Lumpur

Finally, the big night at Dewakan. We arrived at the restaurant with our luggage; we would head straight to the airport afterward.

Darren Teoh, a Malaysian-born chef with a rich Chinese-Indian family background, leads the restaurant. Darren has placed Dewakan on Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants list in 2019, a first for a Malaysian restaurant. After all the introductions and discussions from the previous day, I was more than excited for this dinner.

We arrived early and were asked to wait until the restaurant’s opening time. In the lobby, there was a mandala made of little stones that looked like painted rice grains, forming a complex and colorful geometric pattern. It made me think about the discussions from yesterday’s event. Several speakers talked about the multi layered collaboration journey that a grain of rice takes to seamlessly reach a plate.

We were invited to go upstairs, where we meet Noel.

Ivan had filled me in on Noel, the sous chef—the guy running the daily grind, as opposed to Darren who’s also juggling executive duties.

“Noel’s super disciplined,” Ivan had told me the day before. “You’ll see, the kitchen’s always silent. He’s not mean or anything, just serious and structured. So whenever I come in, I talk as loud as possible, tweak his nipples in front of everyone. They got super annoyed at first but now they take me as I am. It’s my way of dealing with the pressure.”

And now, Noel is giving us a tour of the kitchen. He’s incredibly warm, knowledgeable, and funny. That’s the vibe the team exudes – silent, calm, focused, sharp, and composed professionals.

“We switched from metal to wood furniture here,” Noel explains “Gives a warmer, softer feel to the work environment. Plus, we can’t put hot pots on it, so it makes us work more carefully and mindfully, impacting what we put on the plate.”

Working in restaurants like this one can be incredibly tough. However, once you’ve gone through the 36 chambers of learning, you reach very rewarding states in your work. States that people who’ve spent their lives at desks and say, “I could never do something like that,” will never understand. Yesterday, in the taxi, I was talking with Ivan, reminiscing about the old days at Mugaritz.

“I have very specific memories of many things.”he says “A green field after grilling. Plating moments. A long wait at the train station before leaving for the last time.”

“Yeah, man!” I tell him “It’s been almost twenty years. I remember having quasi-spiritual experiences. Like the plating of the Gargillou,”

“Same,” he said.

A dish with 25 different herbs, 12 petals, and 12 vegetables that had to be assembled with surgical tweezers, piece by piece like a meticulous and intricate ikebana. I remember reaching states of what I would later read described as ‘samadhi‘—a state of meditative consciousness.

After the kitchen walkthrough, Noel shows us the test kitchen brimming with native ingredients.

“These are individual peanuts—they grow solo here. These seeds smell like garlic. These are turmeric flowers. This seed’s poisonous, gotta boil it three times.

“This is long pepper—before chilies came from America, it was the main spice. Chili took over because it’s quicker to produce.”

“This citrus is known as a crocodile egg,” he explained while rubbing it against a stone and inviting us to take a whiff. Noel proceeded to crush leaves for us to smell, providing a cultural tour with each scent. He also encouraged us to touch various textures and products. Most importantly, he shared stories and anecdotes about the producers and the sourcing of these ingredients. There were so many stories that it would be impossible to include them all in this article.

“This rice is grown by a specific ethnic group on flat top hills. See, rice is regulated in Malaysia, and the government only allows certain varieties. But these communities can grow their own because they’ve been doing it for ages. The government-approved rice wouldn’t survive up there anyway.”

“Is everything in the restaurant Malaysian?” I ask.

“Yes, except for the butter in one dish and the wines. You can’t produce alcohol here; only three breweries have a license.”

Then he moves to the dishware.

“All this tableware is upcycled. Look, this one’s made from recycled San Pellegrino bottles.”

He takes us to the shelf of fermentation jars, showing us one after another.

“We use fermentation as an upcycling resource. We take all the trimmings from different seafoods to make garums and such. This one’s sardine. This is mango peel. This one’s squid.”

Sniffing fermenting processes can be a risky game. Funky clouds emerge with each unveiling, some fishy, others leaning toward fruity, but all quite strong in aroma. Each jar he opens releases hints at the feast to come.

“And finally,” he says, “this is nutmeg. Malaysia was a major nutmeg producer, but due to profitability, it was replaced by rubber. However, the nutmeg we’re macerating here is a local variety, nothing like the nutmeg known worldwide.”

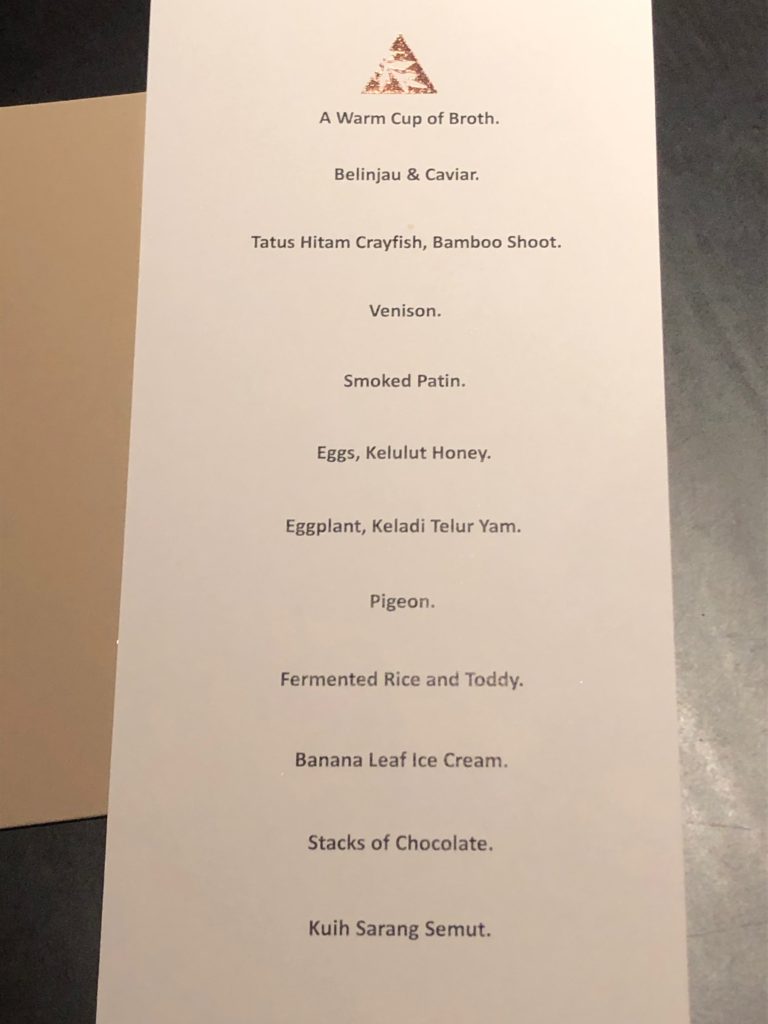

The menu was an adventure, a journey through ingredients, flavors and textures, each course a new chapter in an unfolding culinary tale.

For our first drink, we ordered a sparkling Origarami sake, which was served cold in champagne glasses. Sweet, with subtle notes of freshly steamed sour rice mingling within the crisp bubbles.

The meal kicked off with a crab broth served in a teacup, a sachet of herbs and flowers steeping within, infusing it with aroma. On the side, a banana leather topped with more flowers, a punchy, clear broth that became a festival of flavors with the herbs, while the banana leather offered a smooth, creamy counterpoint.

Next, an origami frog crafted from, a Chinese leaf, once used as a cookie dye, paired with a cream made from belinjau, and a generous dollop of the caviar Ivan had raved about. No doubt, the caviar was amazing, delicate and subtle.

As we prepped for the third plate, Darren himself appeared, sharing more about his domain and introducing the dish.

A taco like no other. The ‘tortilla’ was breadfruit leather, topped with Borneo’s spinous lobster, crayfish, grilled bamboo shoots, and a variety of local herbs like silom leaves and Javanese coriander. Baby pickled cucumbers, tiny as larvae, and torched ginger flowers, all crowned with a wild mangosteen emulsion. This was a taco in its most elevated form, the tiny cucumbers popping among the ingredients, the charcoal aromas of the grilled crustacean.

The next course was like a mille-feuille of dry-aged venison carpaccio from southern Malaysia with chive flower. A walk in the forest. A robust garlic flavor mingled with the herbs, funkily delicious, the deer’s gamey taste striking a fine balance with the strong seasoning. Perhaps a tartar would have worked better with that kind of meat.

Noel had told John during the kitchen tour that Malaysian venison is a whole different beast from the one we know in Europe. It’s a different animal altogether, and its meat is much leaner.

Slices of lacto-fermented water chestnuts came with sticky fruit, smoked patin fish wrapped in tuna leaves, and mambangan syrup. The fish was cooked to perfection, its smokiness not overpowering as found in central and northern Europe, providing a fine contrast to the milder fruits on the plate.

The service unfolds with grace and smiles, accompanied by kind and generous explanations.

Then came one of my favorites. A sardine garum cured egg yolk, paired with durian, sage leaves, stigma bee honey, and clams, alongside ‘forbidden’ rice puffed like popcorn, a technique akin to what’s done with wild rice. A medley of strong sea flavors, sweet funk, and saltiness, it was a joy to eat.The durian was subtle in this one. I didn’t even notice it. I made little tacos with the leaves.

The following dish might have topped the previous one. A gyoza stuffed with a chinese-style creamy eggplant blend. This dish brought back memories of the spicy eggplant I’d had with Ivan. Served with stinky bean miso and nestled on a bettle leaf, the sauce was a piquant pig bean chili, and those singular peanuts we crushed into a paste for dipping.

Darren came over to our table and mentioned that he had been working at Noma back in 2011, the same year as John, but different months. It was clear that the entire culinary proposition here had been influenced by and adapted from the New Nordic Movement to the Malaysian context. In the early 2000s, Claus Meyer, René Redzepi, and a group of Danish gastronomes opened Noma. Shortly afterward, they wrote a manifesto declaring a new cuisine that would redefine the culinary identity of a region that had previously generated little interest. Scandinavian cuisine was synonymous with salmon, and Danish cuisine was not talked about at all back then. The Nordic manifesto defined a new culinary era in which restaurants would dare to cook exclusively and dogmatically with locally sourced ingredients, a new way of looking at food, or even finding food in ways no one ever looked before. Many of these restaurants imported only one product: coffee. Everything else was, with variations from one restaurant to another, sourced locally. This posed a fascinating creative challenge, and chefs started using all kinds of previously neglected ingredients—roots, seaweed, marine species, grasses from the forest, even moss, ants, and bark. Preservation and fermentation techniques became a trend to expand the spectrum of flavors a these new discovered ingredients could achieve.

At Dewakan, Darren plays the same game. Collaborating with communities to obtain remote products, exploring creative boundaries in transforming these ingredients, and redefining a country’s cultural identity. I mean, what more authentic way is there to express a country and its nature than through the products that grow within it?

Next, The Pigeon—oh, mama. Whole grilled birds with an array of micro garnishes: chrysanthemum-like rolled radishes, shire vegetable leaves, chestnut tofu, pickled spring onions, pumpkin miso in a gochujang style, white guava, and a naruto –Those two-colored spiral things you sometimes find in your ramen.– of fish paste. A garnish with fish, yet subtly flavored. The rice, mixed with a buttery paste of—wait for it—more seafood. A surf and turf masterpiece. The pigeons grilled to perfection, heads served to extract the delicate and robustly flavored brains.

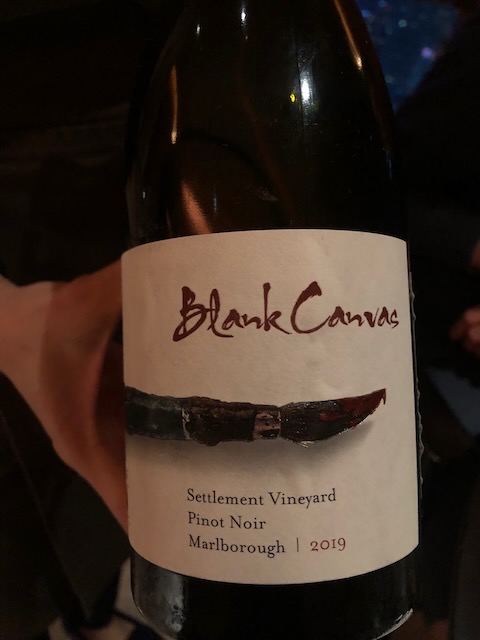

Darren would tell us they use three types of rice for a perfect aromatic blend. Epic. The wine had light fruity and velvety textures of the New Zealand terroir. A tear slid down my cheek as I ate.

John quipped, “Mmmm. Look at all that fat. This bird hasn’t done much flying. Lived its life on a couch watching TV.”

The pre-dessert was a a snow of toddy, which is made by minority communities from the unopened blossoms of the coconut. Each night, their nectar is gathered, and by day, it transforms through fermentation, offering tastes that shift with the sun’s path. This dessert was like eating snow surrounded by water with soft coconut undertones and precise punches of pickled citrus.

One of the highlights was the banana leaf ice cream. Coming from a banana-growing country, I’m familiar with many varieties and the magical aromas of the wildest ones. This took me back to the scents of Venezuelan cambur titiaro or topocho. But the real stunner was, of course, the banana leaf ice cream—fresh and pungent, a far cry from my reference point of smoked plantain leaf. Who thinks to work a banana leaf into an ice cream? Innovation is seeing what nobody else sees in what everyone sees, and here’s where Darren and his team’s inventiveness and audacity shine. A dessert with three simple technical elements, but conceptually and product-wise mind-blowing.

“How do you even describe such a flavor to a European?” we pondered at the table. “It’s tough.”

Darren approached to check on us, and we presented our quandary.

“Well, actually, these are unfamiliar flavors for Malaysians, too. Eating banana leaf isn’t common here—it was something we decided to experiment with, and it worked out,” he explained.

The following dessert was a chocolate cookie mille-feuille interspersed with various local fruits. Fun to eat, though John suffered a bit of durian-induced PTSD.

“Oh no… it’s coming back. I can smell it. This dessert has durian.”

Darren returned with an off-menu bonus: chocolate made without cocoa. They’d processed a native seed just like chocolate, using only two ingredients—the seed and sugar.

He served it both pure and as a hot chocolate alongside with Sarang Semut, a traditional Malay biscuit cooked in an antique mold, with the highest quality mangosteen and various creams to accompany the cake.

“You know,” Darren told us about the whole menu, “this kind of conceptual approach, you can find it with Chele Gonzales in the Philippines, and the guys at Locavore in Bali. They’ve also got a sister restaurant called Nusantara.” This isn’t just a display of generosity, but also a deep understanding that these kinds of initiatives need to grow through regional collaboration with visionaries who share common causes.

Unforgettable—after just a few days in Malaysia, I felt like I’d traversed its land and history through a marvelous dinner, reached through wonderful people.

Buddhists often speak of the interconnectedness of all beings and the importance of mindful action. Just like the intricate mandala in the building’s lobby, every grain of rice on our plates had a story, a journey, and a purpose. The team, under the wings of characters like Darren and Noel, managed to infuse purpose into every dish, like patient artisans in a temple. I’m definitely leaving with a longing to return. Combined with Singapore, this was my first visit to Asia.